|

|

(Editors

Note: Jo Freeman was one of the pioneers of second wave feminism and

edited the first national women's liberation newsletter. She is also

a tireless button collector as this article from Ms

magazine demonstrates. Jo is a contributor of the Herstory Project.) (Editors

Note: Jo Freeman was one of the pioneers of second wave feminism and

edited the first national women's liberation newsletter. She is also

a tireless button collector as this article from Ms

magazine demonstrates. Jo is a contributor of the Herstory Project.)

Published

in Ms. magazine, August 1974, pp. 48-53, 75.

I've

been collecting buttons since 1964 when my local pusher enticed me with

freebies until I was hooked. My passion has waxed and waned with time,

so I now have somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 different buttons --

a paltry number to the serious collector, who usually loses count at

20,000. And I have never quite reached the fervor of some devotees,

who have given up a whole room of their house to store their buttons,

and who have also given up all their spare time and change to collect

them. Like most collectors, however, once I reached the moment of truth

-- the realization that I couldn't collect every button ever printed

-- I had to become a specialist. Since I am a feminist, it was natural

that my ambition would be to have the world's largest feminist button

collection. I now have somewhere between 200 and 250 different feminist

buttons. You might think that with so many, I would feel secure. No

way. Every collection I see, no matter how small, usually contains at

least one button I don't own -- and spasms of unfulfilled desire surge

through my bloodstream. I've

been collecting buttons since 1964 when my local pusher enticed me with

freebies until I was hooked. My passion has waxed and waned with time,

so I now have somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 different buttons --

a paltry number to the serious collector, who usually loses count at

20,000. And I have never quite reached the fervor of some devotees,

who have given up a whole room of their house to store their buttons,

and who have also given up all their spare time and change to collect

them. Like most collectors, however, once I reached the moment of truth

-- the realization that I couldn't collect every button ever printed

-- I had to become a specialist. Since I am a feminist, it was natural

that my ambition would be to have the world's largest feminist button

collection. I now have somewhere between 200 and 250 different feminist

buttons. You might think that with so many, I would feel secure. No

way. Every collection I see, no matter how small, usually contains at

least one button I don't own -- and spasms of unfulfilled desire surge

through my bloodstream.

One of the great

appeals of button collecting -- aesthetics and historical significance

aside -- is the opportunity it gives to pursue impulses one normally

has to repress. It can do this for one simple reason: buttons are, after

all, intrinsically worthless. They are made to be given away in order

to be worn by the greatest number of people. Thus, if you talk someone

into a good (for you) trade, or lift a few buttons from the opposition

campaign headquarters under false pretenses, you're not depriving anyone

of something essential for their existence. Just as contact sports permit

you to physically batter people you barely know, button collecting permits

you to psychologically outwit your colleagues-with the assurance that

it's all in good fun. One of the great

appeals of button collecting -- aesthetics and historical significance

aside -- is the opportunity it gives to pursue impulses one normally

has to repress. It can do this for one simple reason: buttons are, after

all, intrinsically worthless. They are made to be given away in order

to be worn by the greatest number of people. Thus, if you talk someone

into a good (for you) trade, or lift a few buttons from the opposition

campaign headquarters under false pretenses, you're not depriving anyone

of something essential for their existence. Just as contact sports permit

you to physically batter people you barely know, button collecting permits

you to psychologically outwit your colleagues-with the assurance that

it's all in good fun.

Nonetheless, collecting

does have its rules -- the violation of which can lead to ostracism

and disrepute. The greatest sin of all is to counterfeit a button. Noncollectors

see nothing wrong at all in reproducing an old button, and commercial

establishments often reproduce, old Presidential campaign items as advertising

gimmicks. This compels the American Political Items Collectors, the

oldest organization of button collectors, to regularly send out lists

of "brummagem" -- copies of buttons. The Association for the

Preservation of Political Americana, formed almost two years ago, has

pushed to end the creation of buttons purely for private sale to collectors.

Their efforts have been supported by Public Law 93-167, the Hobby Protection

Law, which requires a reproduction of any political item to have the

year of duplication printed on it, thereby distinguishing a copy from

an original item. Nonetheless, collecting

does have its rules -- the violation of which can lead to ostracism

and disrepute. The greatest sin of all is to counterfeit a button. Noncollectors

see nothing wrong at all in reproducing an old button, and commercial

establishments often reproduce, old Presidential campaign items as advertising

gimmicks. This compels the American Political Items Collectors, the

oldest organization of button collectors, to regularly send out lists

of "brummagem" -- copies of buttons. The Association for the

Preservation of Political Americana, formed almost two years ago, has

pushed to end the creation of buttons purely for private sale to collectors.

Their efforts have been supported by Public Law 93-167, the Hobby Protection

Law, which requires a reproduction of any political item to have the

year of duplication printed on it, thereby distinguishing a copy from

an original item.

Buttons first appeared

widely during the Presidential campaign of 1896 and have been a campaign

staple ever since. Celluloid Buttons first appeared

widely during the Presidential campaign of 1896 and have been a campaign

staple ever since. Celluloid

buttons -- using a thin, transparent plastic-like covering to wrap paper

with the printed image on it around a metal, plate -- have become the

most popular. Lithographed buttons -- punched out of a large sheet of

metal upon which mass copies of the button are printed -- are more economical

to produce if done in quantities over 10,000. However, they are less

favored by collectors because few colors are used, designs are simple,

and they easily scratch.

The Women's Liberation

Movement began during the height of the contemporary button craze. Consequently,

buttons reflect the Movement's history and development with greater

consistency than its political tracts. The first new feminist buttons

showed the civil rights origins of the Women's Liberation Movement.

At the 1967 National Organization for Women national board meeting Betty

Farians, then of Bridgeport, Connecticut, appeared wearing a red-on-green

button declaring BAN DISCRIMINATION BASED ON RACE-CREED-COLOR OR SEX.

The sex provision of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was still

being ignored by the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission and virtually

every nonfeminist. Tired of constantly reminding people that discrimination

in employment on the basis of sex was as prohibited as that based on

race, creed, and color, Betty Farians decided to say it with a button.

This was as individual an action as that of Ti-Grace Atkinson, whose

FREEDOM FOR WOMEN button was produced in the winter of 1968. Although

Atkinson was then president of New York NOW, the organization was reluctant

to commit itself to a button. So she took the initiative. The Women's Liberation

Movement began during the height of the contemporary button craze. Consequently,

buttons reflect the Movement's history and development with greater

consistency than its political tracts. The first new feminist buttons

showed the civil rights origins of the Women's Liberation Movement.

At the 1967 National Organization for Women national board meeting Betty

Farians, then of Bridgeport, Connecticut, appeared wearing a red-on-green

button declaring BAN DISCRIMINATION BASED ON RACE-CREED-COLOR OR SEX.

The sex provision of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was still

being ignored by the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission and virtually

every nonfeminist. Tired of constantly reminding people that discrimination

in employment on the basis of sex was as prohibited as that based on

race, creed, and color, Betty Farians decided to say it with a button.

This was as individual an action as that of Ti-Grace Atkinson, whose

FREEDOM FOR WOMEN button was produced in the winter of 1968. Although

Atkinson was then president of New York NOW, the organization was reluctant

to commit itself to a button. So she took the initiative.

The next feminist

button that came to my attention arrived in the mail early in January,

1969. Serving both as editor and as mailing address for "Voice

of the Women's Liberation Movement" (the only national Women's

Liberation newsletter publishing at that time), I was a logical recipient

for news of almost anything that was happening in the Movement. Blue

on white, this button urged that UPPITY WOMEN UNITE. It was produced

for her class by Kimberly Snow, a graduate teaching assistant in a women

and literature course at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks.

She sent me the extras she had, and I mailed them to feminists around

the country. I ostentatiously wore UPPITY WOMEN UNITE so I could offhandedly

inform people that our "chapter" in Grand Forks, North Dakota,

was distributing them. In early 1969, there were only a dozen or so

other cities -- all of them major metropolises -- known to have functioning

feminist groups, so it sounded as though the Women's Movement were making

headway. UPPITY WOMEN UNITE has since become one of the most popular

slogans in the Movement. Dr. Bernice Sandier, of the American Association

of Colleges, carries large quantities of these buttons, which she scatters

around the country like a modern-day Johnny Appleseed. Many other groups

sell them to raise funds. The next feminist

button that came to my attention arrived in the mail early in January,

1969. Serving both as editor and as mailing address for "Voice

of the Women's Liberation Movement" (the only national Women's

Liberation newsletter publishing at that time), I was a logical recipient

for news of almost anything that was happening in the Movement. Blue

on white, this button urged that UPPITY WOMEN UNITE. It was produced

for her class by Kimberly Snow, a graduate teaching assistant in a women

and literature course at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks.

She sent me the extras she had, and I mailed them to feminists around

the country. I ostentatiously wore UPPITY WOMEN UNITE so I could offhandedly

inform people that our "chapter" in Grand Forks, North Dakota,

was distributing them. In early 1969, there were only a dozen or so

other cities -- all of them major metropolises -- known to have functioning

feminist groups, so it sounded as though the Women's Movement were making

headway. UPPITY WOMEN UNITE has since become one of the most popular

slogans in the Movement. Dr. Bernice Sandier, of the American Association

of Colleges, carries large quantities of these buttons, which she scatters

around the country like a modern-day Johnny Appleseed. Many other groups

sell them to raise funds.

Symbol-making is

a necessary part of any social movement; it provides a quick, convenient

way of proclaiming one's views to the world. At the first (and so far

only) national conference of young Women's Liberation groups, held outside

Chicago over Thanksgiving in 1968, an oft-repeated question was: can

we devise an appropriate symbol for a new Women's Movement? What informally

emerged from that gathering was an idea to use a double X in a circle

-- representing the double-X chromosome. No decision-making structure

existed to sanction or even promote this symbol, but the following spring

a group from Nashville who had attended the conference put out a double-X

button surrounded by the words WOMEN'S LIBERATION. It flopped, but another

symbol quickly replaced it-one that caught the popular imagination. Symbol-making is

a necessary part of any social movement; it provides a quick, convenient

way of proclaiming one's views to the world. At the first (and so far

only) national conference of young Women's Liberation groups, held outside

Chicago over Thanksgiving in 1968, an oft-repeated question was: can

we devise an appropriate symbol for a new Women's Movement? What informally

emerged from that gathering was an idea to use a double X in a circle

-- representing the double-X chromosome. No decision-making structure

existed to sanction or even promote this symbol, but the following spring

a group from Nashville who had attended the conference put out a double-X

button surrounded by the words WOMEN'S LIBERATION. It flopped, but another

symbol quickly replaced it-one that caught the popular imagination.

The feminist button

depicting a clenched fist inside the biological female symbol was produced

by Robin Morgan for the second Miss America Pageant demonstration, in

1969. Unlike the double X, it combined the elements of defiance and

revolution with that of femaleness. The original version was a dark

red on a white The feminist button

depicting a clenched fist inside the biological female symbol was produced

by Robin Morgan for the second Miss America Pageant demonstration, in

1969. Unlike the double X, it combined the elements of defiance and

revolution with that of femaleness. The original version was a dark

red on a white

background. It has undergone some regional changes -- Boston's button

is outlined, Chicago's has narrow lines, New Haven's fist crashes through

the top of the female symbol-- but the basic design is the same.

Initially, Robin

Morgan worried over the choice of a red button for this particular demonstration.

Ever conscious that major corporations like to co-opt incipient protest

movements, she imagined that the cosmetic firm sponsoring the pageant

might respond by manufacturing a matching lipstick named "Liberation

Red." Therefore, if we were asked about the button, we were instructed

to reply that the color was "Menstrual Red." No one would

name a lipstick that. Initially, Robin

Morgan worried over the choice of a red button for this particular demonstration.

Ever conscious that major corporations like to co-opt incipient protest

movements, she imagined that the cosmetic firm sponsoring the pageant

might respond by manufacturing a matching lipstick named "Liberation

Red." Therefore, if we were asked about the button, we were instructed

to reply that the color was "Menstrual Red." No one would

name a lipstick that.

Simultaneously,

Cindy Cisler (architect, activist, bibliographer) was creating the equality

pin for the First Congress to Unite Women in New York City in November,

1969. Its simple design -- an equal sign inside a female symbol -- was

inspired by the CORE equality pin and was chosen because it required

no artistic ability to scribble on walls or other convenient surfaces.

It was, therefore, a good guerrilla weapon. The first such pin was a

one-inch white on rust. The colors and size were chosen to match those

of the alpha-symbol button Cisler had already designed for the National

Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws. The alpha-for-abortion

idea was borrowed from the British abortion-law reform group and soon

became the primary symbol of the American repeal movement. The alpha

and equality pins, like the fist, were permuted into endless colors,

designs, and combinations. Simultaneously,

Cindy Cisler (architect, activist, bibliographer) was creating the equality

pin for the First Congress to Unite Women in New York City in November,

1969. Its simple design -- an equal sign inside a female symbol -- was

inspired by the CORE equality pin and was chosen because it required

no artistic ability to scribble on walls or other convenient surfaces.

It was, therefore, a good guerrilla weapon. The first such pin was a

one-inch white on rust. The colors and size were chosen to match those

of the alpha-symbol button Cisler had already designed for the National

Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws. The alpha-for-abortion

idea was borrowed from the British abortion-law reform group and soon

became the primary symbol of the American repeal movement. The alpha

and equality pins, like the fist, were permuted into endless colors,

designs, and combinations.

In 1969 and 1970,

new buttons popped up everywhere. This was the springtime of the Movement

and each new button and each new group gave us hope that we were strong

and growing. New York's Redstockings printed the first SISTERHOOD IS

POWERFUL pin; Seattle Radical Women surrounded a photo of a Vietcong

liberation fighter with the words WOMEN'S LIBERATION; Los Angeles drew

a Statue, of Liberty design with a clenched fist; and San Francisco

used a silhouetted standing figure, which eventually became the logo

of the Women's History Library in Berkeley. In 1969 and 1970,

new buttons popped up everywhere. This was the springtime of the Movement

and each new button and each new group gave us hope that we were strong

and growing. New York's Redstockings printed the first SISTERHOOD IS

POWERFUL pin; Seattle Radical Women surrounded a photo of a Vietcong

liberation fighter with the words WOMEN'S LIBERATION; Los Angeles drew

a Statue, of Liberty design with a clenched fist; and San Francisco

used a silhouetted standing figure, which eventually became the logo

of the Women's History Library in Berkeley.

The first official

NOW buttons -- declaring EQUALITY FOR WOMEN -- were included in packets

distributed to those attending the March, 1970, national conference

in Chicago. NOW buttons, like fist buttons, have also multiplied over

the years. There is an official logo button in black-on-white and white-on-black,

designed by Ivy Bottini, and a variety of equality, fist, and male and

female symbol combinations. The first official

NOW buttons -- declaring EQUALITY FOR WOMEN -- were included in packets

distributed to those attending the March, 1970, national conference

in Chicago. NOW buttons, like fist buttons, have also multiplied over

the years. There is an official logo button in black-on-white and white-on-black,

designed by Ivy Bottini, and a variety of equality, fist, and male and

female symbol combinations.

As the Movement

surfaced in 1970, it began to mark its events with buttons. Chicago

women celebrated International Women's Day on March 8, 1970, with a

striking button that reflected the Third World solidarity concerns of

the anticapitalist, anti-imperialist Chicago Women's Liberation Union.

The Women's Bureau of the Department of Labor put out a button on its

fiftieth anniversary in June of that year. Several buttons were distributed

for the Women's Strike for Equality on August 26, 1970. Expecting a

small turnout, the organizers failed to print enough buttons to meet

the demand of the people who participated in that memorable commemoration

of the fiftieth anniversary of women's suffrage. This forced many groups

to print their own to mark the date. As the Movement

surfaced in 1970, it began to mark its events with buttons. Chicago

women celebrated International Women's Day on March 8, 1970, with a

striking button that reflected the Third World solidarity concerns of

the anticapitalist, anti-imperialist Chicago Women's Liberation Union.

The Women's Bureau of the Department of Labor put out a button on its

fiftieth anniversary in June of that year. Several buttons were distributed

for the Women's Strike for Equality on August 26, 1970. Expecting a

small turnout, the organizers failed to print enough buttons to meet

the demand of the people who participated in that memorable commemoration

of the fiftieth anniversary of women's suffrage. This forced many groups

to print their own to mark the date.

Sometimes buttons

became more impressive than the events they hailed. A striking red-and-yellow

pin was produced as a fund-raiser for a group of women who took over

an unoccupied New York City. building (Fifth Street Women's Building)

to turn it into a women's center. When they got the heat and lights

working two months later, they were forcibly evicted. The Women's National

Abortion Action Coalition printed a multisymbolic button for its grand

march of November 20, 1971. Unfortunately, the button was bigger than

the turnout. Another unsuccessful occasion supported by a magnificent

button was the April, 1971, meeting in Toronto with North Vietnamese

women and several left-wing women's groups. Designed by Kathy Tackney

and Sharon Rose to raise money for the Washington, D.C., Anti-Imperialist

Women's Collective, the button superimposed the female symbol over the

Vietcong flag in the NLF's official colors. Sometimes buttons

became more impressive than the events they hailed. A striking red-and-yellow

pin was produced as a fund-raiser for a group of women who took over

an unoccupied New York City. building (Fifth Street Women's Building)

to turn it into a women's center. When they got the heat and lights

working two months later, they were forcibly evicted. The Women's National

Abortion Action Coalition printed a multisymbolic button for its grand

march of November 20, 1971. Unfortunately, the button was bigger than

the turnout. Another unsuccessful occasion supported by a magnificent

button was the April, 1971, meeting in Toronto with North Vietnamese

women and several left-wing women's groups. Designed by Kathy Tackney

and Sharon Rose to raise money for the Washington, D.C., Anti-Imperialist

Women's Collective, the button superimposed the female symbol over the

Vietcong flag in the NLF's official colors.

The August 26,

1970, Strike for Equality marked the takeoff point of the Women's Liberation

Movement. For the first time, the potential power of the Movement became

publicly apparent as crowds of women spontaneously poured into the streets

of several cities. Afterwards, membership rolls of feminist groups swelled

as much as 50 to 70 percent. And the numbers and varieties of buttons

expanded The August 26,

1970, Strike for Equality marked the takeoff point of the Women's Liberation

Movement. For the first time, the potential power of the Movement became

publicly apparent as crowds of women spontaneously poured into the streets

of several cities. Afterwards, membership rolls of feminist groups swelled

as much as 50 to 70 percent. And the numbers and varieties of buttons

expanded

exponentially, so that even this buttonmaniac couldn't keep track of

them all. It seemed as though every new organization and new issue had

to make its stamp on button history.

Those who think

feminism is only about equal pay should look at even the limited number

of issue's displayed here: advertising, religion, publishing, abortion,

child care, terms of address, rape, sports, employment, marriage, divorce,

education. Those who think

feminism is only about equal pay should look at even the limited number

of issue's displayed here: advertising, religion, publishing, abortion,

child care, terms of address, rape, sports, employment, marriage, divorce,

education.

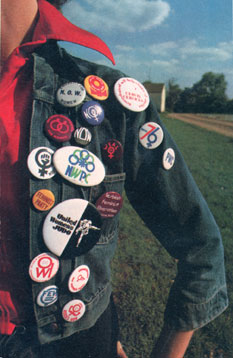

And if anybody

still believes that the Movement appeal's only to a select few, the

wide variety of women's organizational buttons graphically illustrates

how the Movement has spread into almost all corners of American life.

The early ones identified national organizations with lengthy name's

and short acronyms -- the Women's Equity Action League (WEAL), Federally

Employed Women (FEW) Professional Women's Caucus (PWC). Later ones show

how women have organized in traditional female areas -- among nurses,

telephone workers, and airline flight attendants -- and in untraditional

ones -- judo, trade unions, and politics. Special interests within the

Movement -- particularly older women, black women, and gay women --have

also formed their own groups. In buttons, perhaps better than anywhere

else, one can see how these organizations did not erupt overnight but

were the results of years of thinking. Both the National Black Feminist

Organization (NBFO) and the Lesbian Feminist Liberation (LFL) organized

and put out their official button's in 1973. But as early as 1970, a

student at Carleton College in Minnesota had BLACK SISTERS UNITE printed,

and gay women in New York declared that if uppity women should unite,

lesbians should ignite. And if anybody

still believes that the Movement appeal's only to a select few, the

wide variety of women's organizational buttons graphically illustrates

how the Movement has spread into almost all corners of American life.

The early ones identified national organizations with lengthy name's

and short acronyms -- the Women's Equity Action League (WEAL), Federally

Employed Women (FEW) Professional Women's Caucus (PWC). Later ones show

how women have organized in traditional female areas -- among nurses,

telephone workers, and airline flight attendants -- and in untraditional

ones -- judo, trade unions, and politics. Special interests within the

Movement -- particularly older women, black women, and gay women --have

also formed their own groups. In buttons, perhaps better than anywhere

else, one can see how these organizations did not erupt overnight but

were the results of years of thinking. Both the National Black Feminist

Organization (NBFO) and the Lesbian Feminist Liberation (LFL) organized

and put out their official button's in 1973. But as early as 1970, a

student at Carleton College in Minnesota had BLACK SISTERS UNITE printed,

and gay women in New York declared that if uppity women should unite,

lesbians should ignite.

Sometimes the future

comes a little too slowly and our own presumptuousness, or thwarted

hope, is also captured in buttons. In 1969, Jean Witter of Pittsburgh

NOW tried to persuade a reluctant national board, even though it had

endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment, to push for its passage. As part

of her campaign, she distributed an extra large three-color button --

EQUAL Sometimes the future

comes a little too slowly and our own presumptuousness, or thwarted

hope, is also captured in buttons. In 1969, Jean Witter of Pittsburgh

NOW tried to persuade a reluctant national board, even though it had

endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment, to push for its passage. As part

of her campaign, she distributed an extra large three-color button --

EQUAL

RIGHTS FOR WOMEN 26TH AMENDMENT NOW. Unfortunately, time passed her

by. The 18-year-old vote became the 26th Amendment -- and we're still

hoping the ERA will be the 27th.

Despite the lack

of enthusiasm for a fight on the ERA in the late sixties, it has now

become not only one of the most talked-about issues, but also one of

the most buttoned. Many states have put out their own special buttons

for their own ratification campaigns. Despite the lack

of enthusiasm for a fight on the ERA in the late sixties, it has now

become not only one of the most talked-about issues, but also one of

the most buttoned. Many states have put out their own special buttons

for their own ratification campaigns.

How a button can

become a mini-advertising poster and a great fund-raiser is best illustrated

by one particular ERA button. At the January, 1973, National NOW Board

meeting, Nikki Beare of Florida reported that her state's Women's Political

Caucus was giving their blood to raise money for the ERA. Sensing a

good gimmick, Jo Ann Evans Gardner of Pittsburgh, who had already canonized

WE TRY HARDER AND GET PAID LESS, proposed a national blood drive for

the ERA. She and Toni Carabillo of Los Angeles coordinated a drive for

which 1,500 buttons, designed by Joan Nicholson of New York, were printed.

Stating that I GAVE MY BLOOD FOR THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT, each was

available at $10, normally the going price for a pint of blood. At the

end of the year fewer than 100 buttons were left. How a button can

become a mini-advertising poster and a great fund-raiser is best illustrated

by one particular ERA button. At the January, 1973, National NOW Board

meeting, Nikki Beare of Florida reported that her state's Women's Political

Caucus was giving their blood to raise money for the ERA. Sensing a

good gimmick, Jo Ann Evans Gardner of Pittsburgh, who had already canonized

WE TRY HARDER AND GET PAID LESS, proposed a national blood drive for

the ERA. She and Toni Carabillo of Los Angeles coordinated a drive for

which 1,500 buttons, designed by Joan Nicholson of New York, were printed.

Stating that I GAVE MY BLOOD FOR THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT, each was

available at $10, normally the going price for a pint of blood. At the

end of the year fewer than 100 buttons were left.

Button wearing

serves many purposes. The most obvious is that it gives one an opportunity

to make a public statement about strongly felt issues. Letters to the

editor are rarely printed and the chance to make public speeches is

available to only a few, but anyone can wear a button. It's a good way

to start a conversation if you're in the mood to talk and to recruit

if you want to proselytize. Button wearing

serves many purposes. The most obvious is that it gives one an opportunity

to make a public statement about strongly felt issues. Letters to the

editor are rarely printed and the chance to make public speeches is

available to only a few, but anyone can wear a button. It's a good way

to start a conversation if you're in the mood to talk and to recruit

if you want to proselytize.

It's also a good

way to psych people out. I threatened for years to wear a button to

my Ph.D. orals declaring that I AM A CASTRATING BITCH. The time finally

came when I had to put up or shut up, so with some trepidation, I shelled

out for a private button. Wearing it rather timorously on my collar,

I was absolutely amazed at the amount of positive response I got from

other women-especially women who had not previously indicated much sympathy

for the Movement. I was clearly not the only castrating bitch around.

This button, like many others, was not only a statement but a signaling

device. Like an ad in the newspaper, it attracted the attention of those

who were thinking along the same wavelengths. It's also a good

way to psych people out. I threatened for years to wear a button to

my Ph.D. orals declaring that I AM A CASTRATING BITCH. The time finally

came when I had to put up or shut up, so with some trepidation, I shelled

out for a private button. Wearing it rather timorously on my collar,

I was absolutely amazed at the amount of positive response I got from

other women-especially women who had not previously indicated much sympathy

for the Movement. I was clearly not the only castrating bitch around.

This button, like many others, was not only a statement but a signaling

device. Like an ad in the newspaper, it attracted the attention of those

who were thinking along the same wavelengths.

Some of the issues

being wrapped under celluloid are quite complex. WIN WITH WOMEN, designed

by Pepper Petersen for the National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC),

symbolizes a concerted effort to elect more women to public office in

1974. Pat Korbet's SISTER button expresses the solidarity essential

for real changes to be made. Naomi Weisstein's I AM FURIOUS FEMALE and

Betty Farians's MAKE WAR [Women's American Revolution], NOT LOVE bluntly

state some of the inner rage of women toward their status. You can say

things on a button that you often can't confront people with directly. Some of the issues

being wrapped under celluloid are quite complex. WIN WITH WOMEN, designed

by Pepper Petersen for the National Women's Political Caucus (NWPC),

symbolizes a concerted effort to elect more women to public office in

1974. Pat Korbet's SISTER button expresses the solidarity essential

for real changes to be made. Naomi Weisstein's I AM FURIOUS FEMALE and

Betty Farians's MAKE WAR [Women's American Revolution], NOT LOVE bluntly

state some of the inner rage of women toward their status. You can say

things on a button that you often can't confront people with directly.

You can also say

things repeatedly without being repetitive. Flo Kennedy's urgent plea

to DEFEAT FETUS FETISHISTS can be stuck into casual conversation once,

but you can wear it into almost any gathering where it will at least

be read if not agreed with. You can also say

things repeatedly without being repetitive. Flo Kennedy's urgent plea

to DEFEAT FETUS FETISHISTS can be stuck into casual conversation once,

but you can wear it into almost any gathering where it will at least

be read if not agreed with.

If you don't want

to wear someone else's aphorisms, you can easily wear your own. The

next time you think of the perfect squelch five minutes after it was

needed, don't sigh and forget it, button it down. Manufacturers are

listed in the yellow pages under "Badges." If you don't want

to wear someone else's aphorisms, you can easily wear your own. The

next time you think of the perfect squelch five minutes after it was

needed, don't sigh and forget it, button it down. Manufacturers are

listed in the yellow pages under "Badges."

|

|